Almost as old as the human desire for flight is the desire to document it. The development of aircraft generated progress in many areas of human existence – travel, warfare and movement – but it also produced a revolution in vision, allowing the human eye to see their little universe from perspectives that had only been dreamed of before. The history of aerial photography is even older than the history of the aeroplane itself, with the desire to record new perspectives on the ground being contemporary with flying machines predating the motorised plane. Tracking the simultaneously evolving histories of photography and aviation helps us to see how different kinds of technology cater to similar human impulses.

Beginnings in Reconnaissance

Ever since its earliest beginnings, the making of aerial images has been entwined with military operations – both on the battlefield and above it, vision is power. The first ever instance of an aerial reconnaissance operation was during France’s conflict with Austria in 1794, in which hot air balloons were flown and pictures made to gain cartographic intelligence on the front. This was just 11 years after the French invention of the aerial balloon by the Montgolfier brothers in 1783, and the balloon pilots formed one of the first air corps in history.

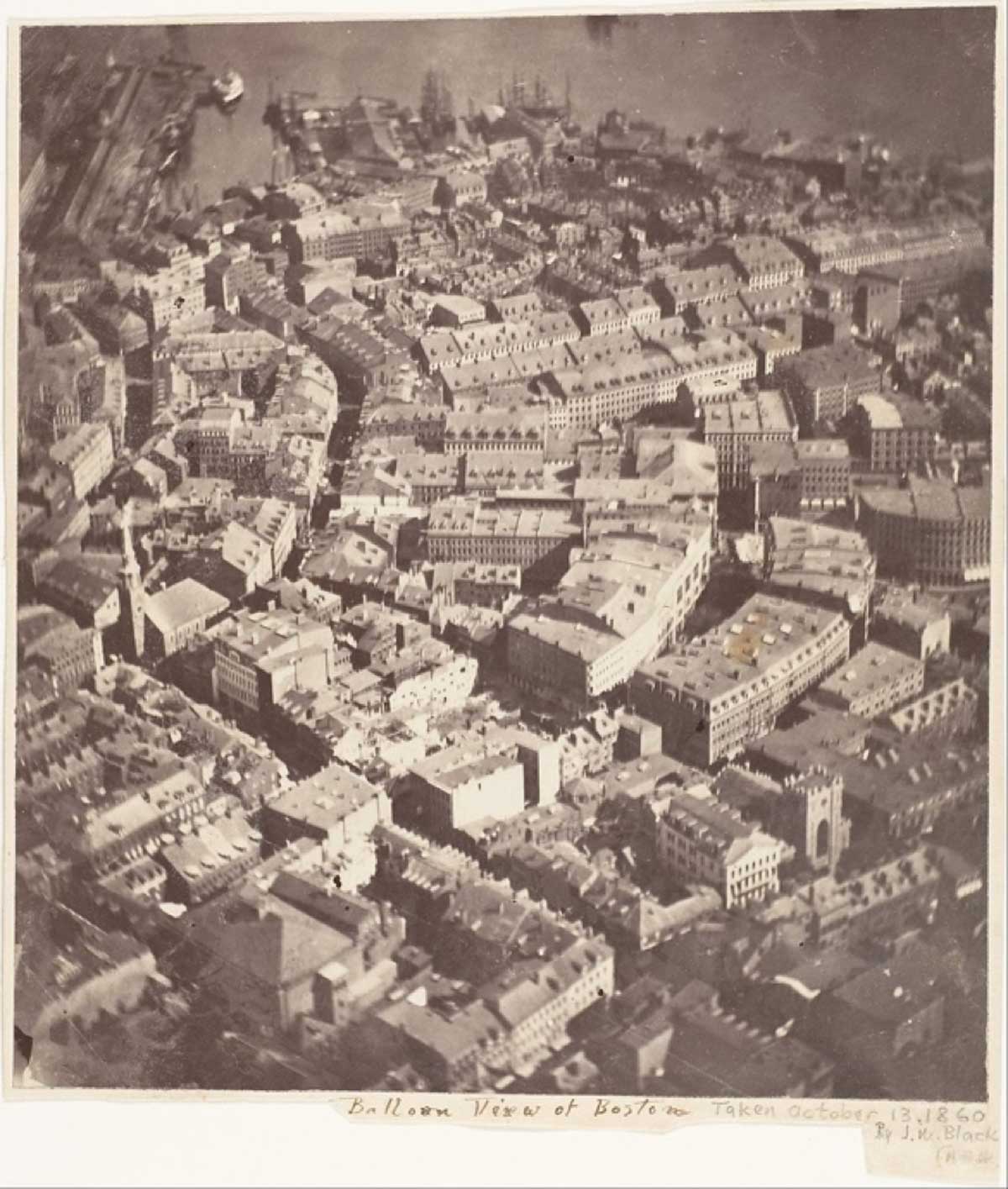

Of course, this is one instance in which aviation had advanced further than image making technology, as the French balloon corps were limited to making sketches. But the 19th century would bring with it the invention of mechanical photography, with the first ever photograph taken in 1826 by Joseph Niecephore Niepce. The desire to capture photographs from the air swiftly followed, and the earliest surviving example of aerial photography dates from 1860: a photograph by James Wallace Black was taken from a balloon of the town of Boston, affectionately named ‘Boston as the Eagle and the Wild Goose See It.’ Later on, a method for taking photographs using cameras strapped to kites was developed by one George Lawrence, a technique responsible for a panoramic photograph of San Francisco Bay in 1906.

[Boston, as the Eagle and the Wild Goose See It, 1860, James Wallace Black. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/283189}

The history of aircraft photography proper begins not much later, in 1908, a mere five years after the Wright Brothers’ first motorised flight in 1903. The plane from which the first ever photograph from an airplane was taken was in fact piloted by Wilbur Wright himself, although it was his passenger, L.P. Bonvillain, who took the photograph on their flight around Le Mans, France. Thanks to their superior mobility with comparison to balloons or dirigibles, and as photographs had moved past the need for the long shutter speeds of the 19th century, motorised aircraft soon became the vehicle of choice for aerial photography.

Unsurprisingly given its military advantages, aircraft photography really came into its own during the First World War, with the birth of reconnaissance aircraft such as Britain’s De Havilland DH-4, introduced in 1917, and used in many different sectors including geological surveys, both in and out of war. Kodak cameras were mounted either inside or outside the rear cockpit, to take photographs for both mapping and surveillance. The First World War was a significant catalyst for the development of aircraft photography techniques, and by 1918 important progress had been made in the results and scope that could be obtained. Throughout the war, over 500,000 aerial photographs were taken on both sides of the conflict.

As aircraft began to extend their reach toward ever higher heights, there was a limit to the potential for photography to be carried out in these more extreme conditions. However, the durability of aircraft cameras were improved as a result of a desire to capture views from these higher altitudes, and in 1928, Britain’s Royal Air Force developed an electric heating system for its cameras, allowing reconnaissance aircraft to take pictures from very high altitudes without the camera parts freezing. In these instances, we see how improvements in aircraft range and power were a catalyst for corresponding developments in photographic hardware.

During World War II, aircraft photography continued to be used for surveillance and mapping. In addition, however, these images shot from aircraft were no longer reserved exclusively for use internal to the military, but became available for public consumption. Aircraft photographs and films became more than just data to be processed, but pictures to be looked at in themselves – appearing across multiple media from newspapers to illustrated propaganda.

WWII also spread the use of gun cameras, used by fighter planes such as the Spitfire in order to measure the effectiveness of attacks, or to provide evidence of enemy craft shot down for pilots’ records, serving to contribute to their claims for ace status. German cameras like the Zeiss Ikon ESK 2000 B were designed especially for use in this way, fitted to Arado Ar 68, and could be installed in the noses of the Messerschmitt Bf 109 and 110. It could also be mounted on the wing. These cameras could be triggered by the firing of the machine guns so as to prove enemy kills, and could capture up to 2000 frames of 16mm footage before needing to be reloaded.

[Picture of the PAC gun camera photograph with link to buy print]

In the context of gun cameras and the reconnaissance cameras before them, aircraft photography was used to record the achievements of human pilots, damaging enemy planes or achieving record heights. In the 21st century however, the technology of live image transmission has become so accurate and instantaneous that in unmanned weapons such as drones, it has come to replace the presence of human soldiers entirely. While photography was used as an aide in the past, supplying troops and strategists with the intelligence required to attack and defend, nowadays, with the use of unmanned drones either pre-programmed or controlled remotely via a computer interface, warfare can be conducted through images alone. Looking back at the use of aircraft photography in the tactics of 20th-century warfare provides important context to the controversial use of drones in war today, illustrating the familiar story that technological progress, in aviation as in imaging, can often leave a dark imprint.